The Russian tennis legend's doping admission evokes memories of the time when Juventus were found to have used legal medicines for bogus conditions to gain a competitive edge

Maria Sharapova's defence for using the banned drug Meldonium is that she was prescribed it for magnesium deficiencies, a heart murmur and a family history of diabetes. She claims to have taken it on and off for 10 years before it came to be placed on the World Anti-Doping Agency's prohibited substance list.

Despite being advised of its impending ban in September 2015, Sharapova claims she failed to read the email, the Grand Slam star continued to use it past the January 1 cut-off date, leading to a positive test at the Australian Open that same month.

While it is plausible that Sharapova did indeed miss a World Anti-Doping Agency memo - an athlete of her profile might be expected to be tested at Grand Slam events and would have at least temporarily halted the program or declared a medical condition in a Therapeutic Use Exemption certificate - her reasons for taking Meldonium for all those years have been treated with suspicion.

Russia has a particular problem with this drug, to which Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko readily admitted after a speed skater and rugby player joined 'Masha' in falling foul of the recent ban.

"I suspect there could be several more cases," Mutko conceded. "Maybe this will wake up our trainers and federation a bit. Unfortunately, a lot of athletes took this medicine."

The drug is available over-the-counter in Russia and other Eastern and Baltic European states, making it a supplement of choice to many professional and amateur athletes. It was a legal medicine in Wada's eyes until January of this year even if it was on the watchlist; no action can be taken retrospectively, only for infringements since the ban.

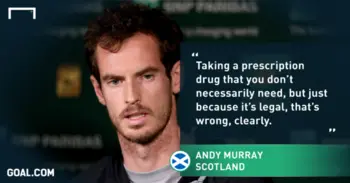

Meldonium may not have been illegal until this year but its benefits nonetheless still gave athletes a sporting advantage, as another tennis star - outspoken doping critic Andy Murray - stated following Sharapova's televised mea culpa.

“I think taking a prescription drug that you don’t necessarily need, but just because it’s legal, that’s wrong, clearly,” the two-time Grand Slam winner said this week.

“If you’re taking a prescription drug and you’re not using it for what that drug was meant for, then you don’t need it, so you’re just using it for the performance-enhancing benefits that drug is giving you. And I don’t think that that’s right."

This practice of using legal medicines to confer sporting advantage has a precendent in football - the hyper-successful Juventus side of the mid-1990s.

Juventus will probably never be asked to hand back the titles they won between 1994 and 1998, even though a court of law ruled that their doctor Riccardo Agricola administered hundreds of doses of legal medicines which gave Juve players performance-enhancing boosts thanks to their 'off label' benefits.

Roma coach Zdenek Zeman called for Italian football to "get out of the pharmacy" in a 1998 interview with L’Espresso and claimed drug use was rampant in Serie A. In particular he referenced Juventus players Gianluca Vialli and Alessandro Del Piero, whose improved physiques ‘surprised’ him.

The Public Attorney of Turin, Raffaele Guariniello, was sufficiently persuaded to launch an investigation into alleged doping practices at the club. His findings led him to order a raid on club premises, a raid which turned up 281 pharmaceutical substances.

Most were approved for use by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) - although at least five anti-inflammatory drugs contained prohibited substances - but the sheer quantity of medicines raised alarm. Gianmartino Benzi, the Public Attorney’s medical advisor, said that the club was stocked as well as any "small hospital".

Agricola and Juventus managing director, Antonio Giraudo, were charged in January 2002 with supplying drugs to their players between July 1994 and September 1998 – one of the most successful eras of Juventus' history. During that time they earned three Serie A titles, the Champions League and the Intercontinental Cup.

The substances were indeed acknowledged to be legal but given to produce the same effects as banned performance-enhancing drugs.

Samyr, an anti-depressant, was found to be used by 23 players. Neoton, for heart conditions, was taken by 14. It is the same drug which was filmed being pumped into the arm of Parma’s Fabio Cannavaro ahead of the 1999 Uefa Cup final against Olympique Marseille. Voltaren - a painkiller and anti-inflammatory drug – was used by 32 players in a "planned, continuous and substantial" way.

A court-appointed witness, pharmacologist Eugenio Muller, stated there was ‘no therapeutic justification’ for the administration of these prescription drugs.

The drugs were used in a similar manner to Meldonium before Wada outlawed its use this year. That product was on the Wada monitoring programme in 2015 while tests were completed on its performance-enhancing capacities. Sharapova’s claimed ignorance seems a feeble excuse.

The Juventus trial lasted nearly two years with superstar players called as witnesses – Zinedine Zidane and Del Piero among them. Other players refused to give evidence citing ‘confusion’, ‘memory loss’ or ‘too many people in the court’.

Agricola was initially handed a 22-month suspended sentence for the supply of performance-enhancing drugs and barred from practising for the same amount of time. The Italian Olympic Committee (Coni) then sought the advice of the Court of Arbitration for Sport over whether or not Juve should be stripped of their titles.

What came back was controversial: “The use of pharmaceutical substances that are not expressly banned by sporting law and that are not similar to illegal substances cannot be punished by disciplinary action,” CAS ruled. That decision partly enabled Agricola and Giraudo to appeal their convictions of sporting fraud and they were subsequently cleared. It is also a CAS precedent which should protect Sharapova from any punishment for historic use of Meldonium, although her reputation cannot be shielded from the damage of doping.

In 2007 Italy’s Court of Appeal concluded that Agricola and Giraudo had committed sporting fraud by administering legal drugs for ‘off label’ performance-enhancing reasons. Prosecutors, though, could not appeal the pair's acquittal but only because of the statute of limitations – too much time had passed since the alleged offence.

Guariniello declared it a "great victory" because the ruling implied the defendants were guilty. The club itself was exonerated only because of insufficient evidence but the judge said Agricola "could not have acted alone".

“Either the players were always sick or else they took drugs without justification… to improve performance," a witness at the trial stated.

Ethically if not legally, that was doping. The dubiousness of their achievements will linger. And that might sound familiar to followers of the Sharapova case.

- Goal