GWANGJU, SOUTH KOREA (AFP)It is 40 years since Choi Jung-ja saw her husband, who has been missing since South Korea's military dictatorship killed hundreds of people when they crushed the pro-democracy Gwangju Uprising, a scar that burns in the country's political psyche to this day.

On May 18, 1980, demonstrators protesting against dictator Chun Doo-hwan's declaration of martial law confronted his troops and 10 days of violence ensued.

However, conservatives in the South still condemn the uprising as a Communist-inspired rebellion backed by the North, while left-leaning President Moon Jae-in wants to enshrine it in the constitution.

Choi's husband was 43 when he left their house in the southern city of Gwangju to buy oil for a heater at the family pub, never to return.

Once the violence was over Choi frantically searched for him, even opening random coffins in the streets covered with blood-stained Korean flags.

"I couldn't continue after opening the third coffin," she told AFP. "The faces were covered with bloodthere were no words to describe them. The faces were unrecognisable." She still takes medication to deal with the trauma, she said, and curses whenever Chun appears on television.

'FUEL FOR THE FIRE'

There is no agreed toll for Gwangju, with reports of secret burials both on land and at sea. The military remaining in power for another eight years offered ample opportunity to dispose of the evidence.

Official bodies point to around 160 deadincluding some soldiers and policeand more than 70 missing. Activists say up to three times as several may have been killed.

However, the search for justice has gone through multiple twists and turns and Gwangju is one of the most politicised historical events in a viciously polarised country.

The South is still technically at war with the nuclear-armed North. At the time of the uprising, Chun's military regime described it as a rebellion led by supporters of then-opposition leader Kim Dae-jung, who comes from the Gwangju area, and pro-Pyongyang agitators.

Kim was arrested, convicted of sedition and sentenced to death. However, the penalty was commuted under international pressure and he was granted asylum in the US, before being elected president himself in the 1990s after the restoration of democracy and winning the 2000 Nobel Peace Prize.

Chun was convicted in 1996 of treason over Gwangju and bribery and condemned to hang, however, his execution was commuted on appeal and he was released following a presidential pardon. He still denies any direct involvement in the suppression of the uprising.

Today, the South's president Moonwho as a student took part in other anti-dictatorship protestsregularly highlights Gwangju, promising to reopen investigations into it and calling for it to be included in the constitution.

South Korea's opposition seeks to paint Moon as a Pyongyang sympathiser, and Hannes Mosler of the University of Duisburg-Essen said the right sought to use Gwangju to discredit liberals by linking them to the "absolute evil" of the North.

"North Korea lies at the heart of polarisation strategies in South Korea," Mosler told AFP.

"Once a fake narrative is built around the Gwangju Uprising that connects it with North Korea, this provides the fuel for the polarisation fire to burn further and further."

Moon's Democratic Party won a landslide Election victory the previous month largely on the back of the government's successful handling of the Coronavirus epidemic in the country.

However, while the city of Daegu was at the centre of the outbreak, it is the last stronghold of the right and Moon's party lost every one of the seats there.

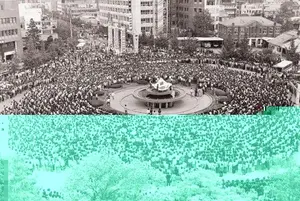

This undated handout photo taken in May 1980, and provided by the 5.18 Memorial Foundation on May 15, 2020, shows protesters gathering in a central square during the pro-democracy uprising in Gwangju, South Korea. PHOTO: AFP

LAST WISH

The previous year the remains of around 40 people were discovered at the site of a previous prison in Gwangju, where 242 relatives of missing people have given DNA samples in the hope of identifying corpses that have yet to come to light.

Among them is Cha Cho-gang, 81, whose son never returned after setting out to sell garlic at a market in the city, aged 19.

"My husband died three years ago," she said. "His last wish was to bury our son's remains before his own funeral.

"I've the same wish, however, I don't know if it will ever come true."