Celebrating the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to Congress in 1870, which granted Black people the right to vote, Robert spoke before an audience of Black and white people at a Cincinnati jubilee and offered his own prophecy, his creed: “Knowledge is power; and those who know the most, and not those who have the most, will govern this country. Let us combine and associate and organize for this end. In the pulpit, in the press, in the street, everywhere let our theme be education, education; until there can't be found anywhere a child of us that is not at the school. With this endeavor carried out, who can measure the progress that may be made in a single generation by a poor, despised, and enslaved race? Then, indeed, would vanish prejudice; then would the noble martyrs of our cause not have died in vain, and human slavery would evermore be an impossibility.”

Robert believed those words. He imagined his son, Robert James Harlan—whom he named after James Harlan—living on equal terms with the scions of privileged white families. Robert Jr. attended Cincinnati’s largely white Woodward High, where he was classmates with William Howard Taft, and went on to college and law school.

Robert raised his son nearly on his own, and also served as a backstop for the extended Harlan family. When John’s older sister, Elizabeth, got married, Robert presented her with the most extravagant of presents, a handmade piano. Afterwards, when one of John’s brothers, James Jr., became destitute and an alcoholic, Robert stepped in with multiple levels of support. “Bob Harlan has for two years been unusually kind to me, not, however, putting me under any obligation,” James Jr. reported to John.

In John’s case, Robert’s gift was political help—and he was ideally positioned to help John gain credibility with Republicans who doubted his conversion to their party after the Civil War. In the first dozen years after the surrender of the Confederacy, African-Americans were an important Republican constituency, and Northern Republicans were wary of Southern efforts to push Black people back into positions of subjugation.

In that atmosphere John became entangled in a scandal that jeopardized his national aspirations. It was 1871, and John was in the midst of a futile campaign for governor of Kentucky under the Republican banner. He loyally and steadfastly defended the national party even though it was held in contempt by much of the Bluegrass State. Still, several northerners could only remember the fact that he was from a slave-owning family and had criticized abolitionists before the war. Then came an incident in which John’s drunken cousin from his mother’s side of the family shot a prominent Black federal official in Washington. Though the motive may have been personal—the Black official was advising a person who wanted to sue the cousin over the sale of a faulty stove—several in the Black community saw the case in starkly racial terms.

At the time, judicial matters in Washington were handled by the federal government, and it happened that John’s good friend from Kentucky, Benjamin Bristow, was President Ulysses Grant’s solicitor General. When the lawyer for John’s cousin let it be known that he had appealed to John for help, several Black leaders smelled a rat. On the hustings in Kentucky, John looked unaware of just how harmful to his future ambitions those rumors could be.

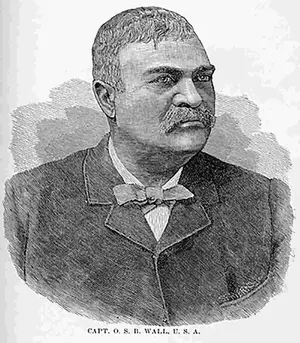

When a drunken cousin of John’s shot the renowned Black leader O.S.B. Wall, John’s reputation was tarnished. Robert stepped in to smooth the waters with Black leaders, preserving John’s image in the Republican Party. | O.S.B. Wall in Joseph T. Wilson’s The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States (1890).

Robert did, and rushed to the capital from his own home in Cincinnati to quell the damage. The victim, Orindatus S. B. Wall, was a Civil War veteran and fellow member of the African-American elite. Wall’s brother-in-law was John Mercer Langston, the founding dean of Howard Law School. Robert was friends with both of them, along with Amanda Wall, who believed her husband had been shot “because he was a colored man and held an office,” as Robert frankly reported to John.

Robert suggested the whole situation was more serious than John believed, noting that Langston—who had the clout to raise a ruckus—believed that “you had written to the president and … authorized other parties to draw on you for large amounts of money for the purpose of clearing” his cousin James Davenport.

Robert proposed a different approach. He defended John to Black leaders in Washington as guilty of nothing more than attempting to spare his family from embarrassment. But, Robert assured them, John had no illusions concerning the wrongness of his cousin’s actions. Robert, too, had known Davenport “nearly from childhood” and described him as having been damaged by the war, in which he fought on the Union side. Robert then brokered a deal: If Davenport were to go free, the Harlan family would guarantee that the troubled man would never set foot in the District of Columbia again. Thus, he would plead guilty to assault with an intent to kill, but President Grant would pardon him on the grounds that he wasn’t in possession of his faculties. The Walls and Langstons kept quiet, and the Harlans satisfied their end of the bargain.